PLA Tremors and the Chairman in Charge

A guest post by Holly Snape on the Chairman Responsibility System

I am glad to be able to publish another guest submission from Holly Snape, a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Glasgow. Before moving to Scotland, she was a fellow at the Research Centre for Chinese Politics at Peking University’s School of Government where she studied Chinese domestic politics and political discourse. Her current research focuses on the relationship between the Communist Party and the State.

In this article, Dr. Snape discusses the Central Military Commission Chairman Responsibility System 军委主席负责制, which has been in the news recently as Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli have been accused of “seriously trampling on and harming the Chairman Responsibility System 严重践踏破坏军委主席负责制”.

This article ignores the salacious rumors and does not try to guess as to what Zhang and Liu really did to trigger their downfalls, but I agree with her that it is important to try to understand the institutional perspective:

In the days following the Zhang/Liu announcement, analysts have discussed elite relationships, visual media footage, “inside information,” and patterns of previous purges. They have invoked sweeping political science theories and revisited comparisons to Stalin. An institutional perspective is lacking. Examining publicly available Party and military documents sheds light on what was purportedly undermined. While this won’t resolve the “why” question, it is a basic—yet so far overlooked—piece of the puzzle for testing assumptions and speculating on the question of “with what implications?”

I hope you find this to be a useful addition to our attempts to understand what might be going on - Bill

PLA Tremors and the Chairman in Charge by Holly Snape

On the same day the news hit that Central Military Commission (CMC) Vice Chairman Zhang Youxia and member Liu Zhenli had been placed under investigation, a PLA Daily editorial accused the two men of “seriously trampling on and harming the Chairman Responsibility System” (严重践踏破坏军委主席负责制)1. This is largely viewed as a claim of their having “undermined Xi’s authority” or challenged his desire for personalized power.

Put aside whether Zhang and Liu did in fact do any “trampling.” What is this “System”? Why does it matter? Does it really boil down to a statement of who’s the boss? And why should it be factored into calculations about the implications of Zhang and Liu’s downfall?

For Xi, the Chairman Responsibility System (中央军委主席负责制) is a big deal. He has been incrementally building it for 13 years. Over this time, dozens of formal documents have been issued and revised and wave after wave of activity has sought to hammer home new rules and demand compliance. The System’s discourse and mechanisms do multiple things at once: entrench and legitimise top-level power structures; enforce decisions from the top; and defend against pushback on Xi’s military reforms—employing study campaigns, disciplinary mechanisms, and the “jurisprudence” of rulemaking.2 The System matters because it is about the Party’s undivided, uncontested control of the military, and about how—as well as by whom—top decisions are made and enforced.

In the days following the Zhang/Liu announcement, analysts have discussed elite relationships, visual media footage, “inside information,” and patterns of previous purges. They have invoked sweeping political science theories and revisited comparisons to Stalin. An institutional perspective is lacking. Examining publicly available Party and military documents sheds light on what was purportedly undermined.3 While this won’t resolve the “why” question, it is a basic—yet so far overlooked—piece of the puzzle for testing assumptions and speculating on the question of “with what implications?”

Transforming Top Power Structures

Xi has used the concept of a “Chairman Responsibility System” (hereafter “CRS”) to delegitimise past practices at the highest levels of power and close legislative and practical loopholes. At this level, three sets of outcomes stand out: one inside the Party relating to Party-army relations; one between Party and state; and one inside the CMC itself.

Xi Era Party discourse frames the CRS as the “fundamental mechanism for realizing” absolute Party leadership of the military.4 Xi uses “CRS” doctrine to entrench the norm of the General Secretary concurrently serving as CMC Chairman. This use of CRS doctrine discredits the past practice of having a second power centre within the Party who legitimately represents “the Party’s” will in the military. 5For three decades between 1981 and Xi’s accession to General Secretary, a two-leader setup had prevailed for over a third of the time.6 In 1987, Party Charter revisions had removed the requirement that the CMC Chairman be chosen from among Politburo Standing Committee members7, allowing broader power sharing8 and creating potential uncertainty in the chain of command between Party and military. This meant that from autumn 2002 to 2004 Jiang—no longer even a Central Committee member—could represent the Party as CMC Chairman while Hu was Party boss. Today, under CRS doctrine, there can only be one top-level representative of the Party’s will to be imposed on the military.

Between Party and state, the CRS removes loopholes, aligning Party CMC rules with those of the state. China has two Central Military Commissions: the People’s Republic of China (PRC) CMC and the Party CMC. They are essentially, but not entirely, the same thing.9 Technically, the Party CMC is formed by the Party Central Committee; the PRC CMC (made up of the same people) is “voted in” by the National People’s Congress. Meetings of these bodies do not happen at the same time, meaning that after the Party ratifies the selected Party CMC Chairman, Vice Chairmen and members, there is a 4–6-month wait until they are ratified as PRC CMC members. Though the PRC Constitution has stipulated the practice of the CRS since 1982—clearly referring to the PRC CMC—until 2017, the Party Charter omitted to mention it. The discrepancy left a technical area of potential doubt: what happens in a crisis if the current Party CMC Chairman is not yet PRC CMC Chairman? Does the CRS system hold up in such a way as to ensure absolute Party leadership of the military? If the two nominal CMC Chairmen were to have opposing views in a crisis, could support build around the PRC CMC Chairman? Xi’s 19th Party Congress Charter revisions plugged that hole.10

Inside the CMC, major reforms, reinforced by previous rounds of dismissals, are combined with new concrete rules to transform the division of authority and norms of decision making. Military reforms during Xi’s first two terms are framed as part of strengthening the CRS. The past CMC composition, which included the four heads of the general departments, changed when those general departments were disbanded. This created a more direct chain of command from the Chairman to the theatre commands by removing the general departments as a potential obstacle—the senior officers of which often “had too much power and were not always responsive to orders from the center.”11

Under Hu, and to some degree under Jiang, the CMC Vice Chairmen had significant autonomy and authority.12 After former Vice Chairmen Guo Boxiong and Xu Caihou were put under investigation their behaviour was condemned13 as having “undermined the substance of and weakened” (虚化弱化) the CRS, in part by “monopolizing power and using it with no restraint (擅权妄为). Even if now-disavowed practices were regarded as legitimate at the time, retrospective application is a basic underpinning of the logic of Party rules.14 Guo and Xu were subsequently used to exemplify why “complete, scientific, effective mechanisms” were needed for CRS to be enforced.15

Under Xi, revised regulations reportedly detail distinctions between the authority of Chairman and Vice Chairmen, stipulating that “Vice Chairmen assist the work of the Chairman.” Executive and expanded CMC meetings, and their agendas, must be approved by the Chairman, who must also chair them himself or delegate a Vice Chairman to do so. For Vice Chairmen and members to leave Beijing on troop inspections, the Chairman must first sign off on it.16

Serving Decision-making, Streamlining Chains of Command

The CRS is not just a rule about ultimate authority over top-level decisions or a way of closing loopholes; nor is it just a mantra-like statement learnt and dutifully repeated throughout the military to remind of who’s boss. It is also a set of mechanisms which attempt to address how reliable, accurate, timely information feeds up and how decisions, once made, feed back down. In other words, it is both a fundamental principle and a system designed to facilitate the Chairman’s decision-making and -enforcement.

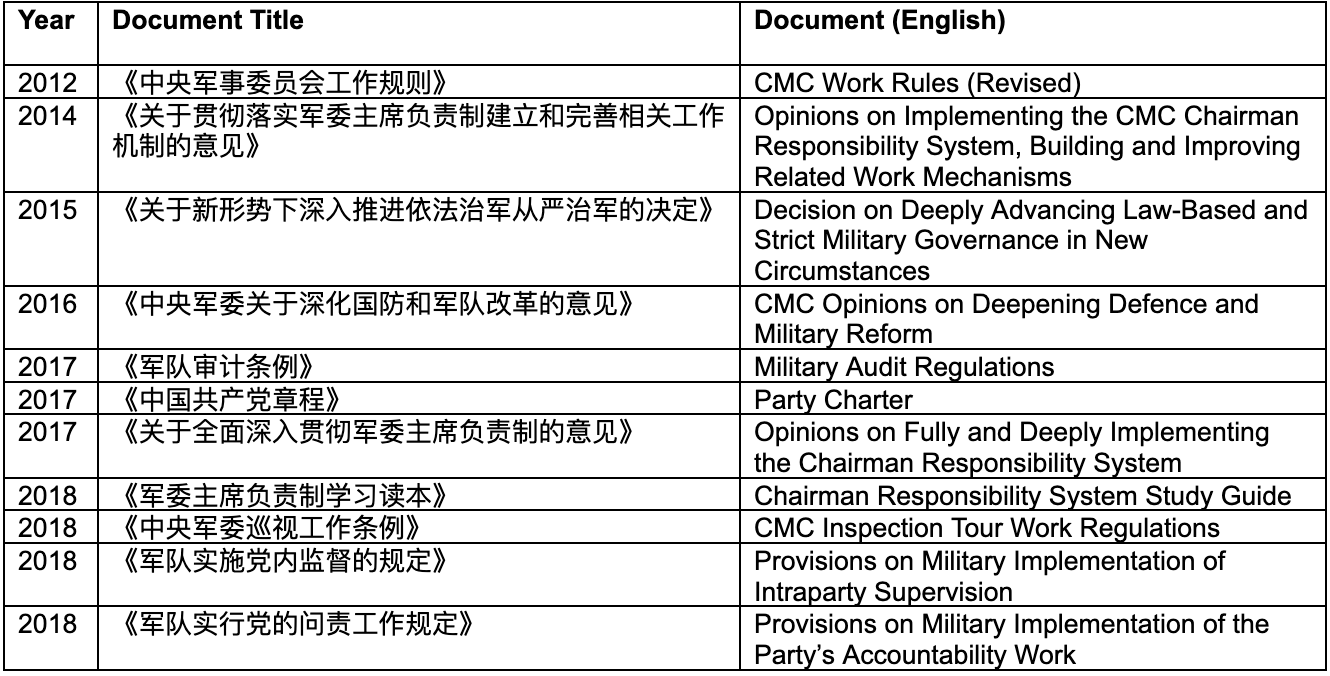

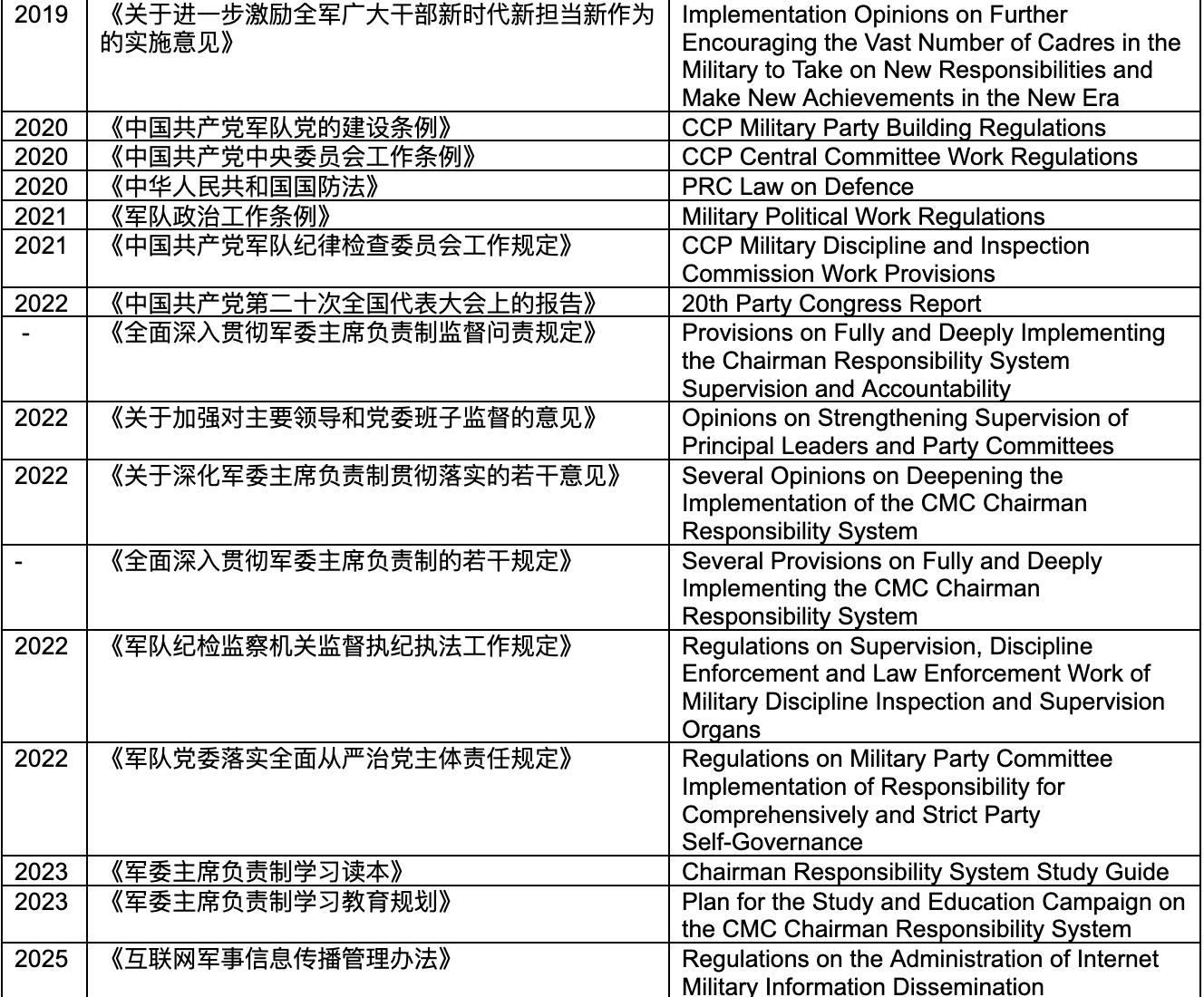

Though open-source information on the Party’s military documents17 is more limited than that on much of the Party’s regulatory system, there is enough to go on to sketch the long (ongoing) process of institutionalising the CRS. Collated into a table at the end of this article, and accounting for document type (which gives a sense of legislative force and level of detail or abstraction)18, the documents which we have public information on give a sense of the concrete rules, mechanisms, and systems of the CRS. It sheds light on how Xi has incrementally built the System’s substance through rulemaking, legislating, disciplinary system building, educational campaigns, and inspection tours.

Under Xi, the CRS involves building “a closed circuit” of mechanisms to enforce the principle that the “CMC Chairman is responsible (负责) for all CMC work, commanding the country’s armed forces, [and] deciding all major questions of national defence and military building.”19 This is combined with a “responsibility system” (责任体系) to make clear who, at what level, is accountable for enforcement.20

The building of this system began in November 2012, at the first Executive Meeting of Xi’s post-18th Party Congress CMC, with revisions to the CMC Work Rules (《中央军事委员会工作规则》)21, which added the principle of practising the CRS. “Rules” (规则) are a detailed and concrete form of regulation. Though not publicly available, a China Leadership Science article cites the CMC Work Rules as stipulating on the “major items” decided by Chairman (which in turn may inform Instruction Requesting and Reporting rules):

“Major items in the CMC’s work, including troop operations and command; appointment and removal of senior officers, and rewards and punishments within the CMC’s authority22…must be approved by the CMC Chairman. All official documents issued in the name of the CMC must be reviewed and signed by the CMC Chairman.”23

A 2014 regulatory document24 reportedly introduced the basic thinking on using “Three Mechanisms” to put CRS into practice: instruction requesting and reporting (请示报告), supervisory urging and inspection (督促检查) and information services (信息服务).

The Party has long used “Instruction Requesting and Reporting” (IRR) throughout the Party and state. Xi has revived and strengthened its use both to help himself and higher levels remain informed of problems on the ground and to press lower Party organizations to comply with central commands and state agencies to align their activities with Party Centre thinking.25 Party IRR works by requiring lower ranking Party organizations (such as those inside state or military entities) to follow strict protocol to request instructions from a designated higher ranking Party organization, then to report back up on implementation. Building or improving IRR systems tailored to put the CRS into practice is intended to facilitate26 both the Chairman’s decision-making process and his command over the military (and the People’s Armed Police), feeding accurate information upwards and creating reporting loops mandating timely information on enforcement.27 In the CRS trinity of mechanisms (三项机制) IRR is combined with “supervisory urging and inspection”—using checks, reviews, and supervised correction mechanisms—and “information services” requiring broadened and better regulated reporting channels and verified, well-selected “useful” information.28

Such mechanisms should be understood in the context of broader institutional reforms. For instance, following the 2016 transformation of seven military regions into five theatre commands, CCP Military Party Building Regulations29 established “Theatre Party Organizations” (战区党委) as a type of Party organization in their own right. This allowed for new stipulations on which Party organization(s) Theatre Party Organizations answer to and direct during “battle tasks,”30 creating a mechanism by which clear Party lines of command inside the theatre commands can be shifted for accomplishing a mission.

To aid enforcement, the process has reshaped the Party’s internal military supervision and accountability systems, instituting a package of regulations buttressed by inspection tours.31 Failure to comply with CRS—both the spirit of the principle and its concrete mechanisms—is made a punishable offence and a focus of special inspection tours. For instance, issuance of a package of 2018 regulations (see Table 1) was accompanied by CMC deployment of six inspection teams in a “Special Inspection Tour on Full, Complete Implementation of the CRS.”

Greater Efficiency, Less Limits?

Rules matter to Xi. Over his three terms he has used rulemaking and institution building as a central part of his approach to transforming the Party itself and the way it controls the state and society. He has not just declared that “the Party leads everything”32 but has pursued its realization—“in every field, every aspect, every node”—in concrete terms.33 Formal rules matter to Xi because he recognizes that they can shape the informal rules of the game—they can be a help or a hindrance, both facilitating and limiting his space to manoeuvre and make demands. His incremental steps to develop the CRS spanning all three terms as Party boss tells us that the CRS also matters.

Examining the CRS system does not answer why Zhang and Liu were brought down but it is a necessary exercise before any speculation on what comes next. Take the argument that by gutting the CMC, Xi has created critical weaknesses in decision making at the top. This is based on the assumption that the removed members of the CMC were crucial to that decision making and could form some degree of constraint on the Chairman himself. The reasons for regarding them as crucial—deep expertise, conflict experience, the presumed ability to “speak truth to power”—all make sense. But judgements on the extent, nature, and points of any resulting weaknesses need to be weighed against factors which have, whether as intended or not, changed the calculus in terms of how decisions are informed, made, and enforced.

In terms of the conditions for forming decisions, access to prompt, accurate, quality information is key. The CRS on paper seeks to ensure this. We may not know whether, in implementation, it works as intended but we can at least factor in the potential influence of information assurance mechanisms in considering the implications of a gutted CMC. In terms of the extent to which there is a difference of opinion among figures with the authority to make it count, there are two key actors to account for, the Chairman and the CMC itself. From an institutional perspective, the latter was already weakened by the institutionalization of the CRS. The Zhang/Liu removal continues the trend. In terms of decision enforcement channels, while figures like Zhang in the past had an outsized influence, the institutionalization of the CRS combined with sweeping military reforms has already gone a long way to removing this as a potential obstacle. The disbanding of the General Staff Headquarters, Xi’s assumption of the role of Commander-in-Chief (总指挥) of the Joint Operations Command Centre (JOCC, 中央军委联合作战指挥中心), and the JOCC’s subsequent shift in status34, appear to have replaced a model reliant on the old general departments and even on bodies like the CMC Joint Staff Department (which Liu Zhenli headed), giving Xi a more direct channel to issue commands. In terms of decision enforcement expertise (in battle), though the CMC’s own pool of expertise has shrunk, military reforms and CRS institutionalization have already placed greater weight on expertise in the theatre commands to translate top-level commands into enforceable action.

Xi has used the CRS not just to delegitimise past approaches to Party command of the gun but to facilitate his top-level decision making, shorten and strengthen the Party’s internal lines of command, and better supervise compliance. Whether the institutionalisation of this new rule system has worked as intended or not, its very creation changes the way decisions are made and enforced.

The CCP-led system is not one which removes powerful people primarily through impartial application of brightline rules. Rules are applied in various tailored ways to explain a removal, build legitimacy around it, and use it to change ideas and expectations of accepted behavioural norms. Though likely not a primary reason for Zhang and Liu’s downfall, the “shock” which commentators have expressed at the swift and “unprecedented” nature of their removal is part of the logic of the system (which gains authority through uncertainty, selectivity, and the deployment of shock and humiliation). While it might harm morale in some quarters, it may also provide ballast for New Era rule enforcement.

24 Jan 2026, 解放军报社论:坚决打赢军队反腐败斗争攻坚战持久战总体战 [PLA Daily Editorial: Resolutely Win the Decisive, Protracted, Total War on Corruption in the Military] https://www.news.cn/politics/20260124/eb3148439da1428788846c2c5516cba1/c.html.

The requirement to comply with “the Chairman Responsibility System” means that to question a decision on military reforms could be regarded as a fundamental form of disloyalty and disobedience.

Only a small number of the regulations and documents cited below can be accessed publicly in full. I also draw on “responsible leader” press Q&A’s, official news reports, newspaper articles, and academic articles.

See the 2015 Decision (Table 1); see also the resolution from the 19th Central Committee’s Fourth Plenum.

Understood as an arrangement established by Deng following June Fourth 1989, when Jiang made way for Hu take over the Chairmanship, Jiang called the “trinity” (三位一体) of one person concurrently serving as Party, state, and military heads “necessary and the most appropriate way,” see 江泽民:我的心永远同人民军队在一起 [Jiang Zemin: My Heart is Forever with the PLA]. Xi’s relentless discursive and legislative campaign has all but institutionalized this.

In 1981 Deng became Chairman while Hu Yaobang was General Secretary. Neither Hu Yaobang nor Zhao Ziyang acted as Party CMC Chairman while in the role of Party General Secretary. In late 1989 Jiang became CMC Chairman following his assignment to Party General Secretary earlier that year. This also accounts for the lag between Jiang stepping down from each position.

See Party Charter 1982 Art. 21 as compared with Party Charter 1992 Art, 22, and中国共产党章程部分条文修正案(1987) [Amendments to Certain Articles of the CCP Charter (1987)].

As well as allowing Deng to remain CMC Chairman.

Though they are often referred to as “one agency, two names” (“一个机构,两块牌子”) this is not quite accurate.

In addition to the insertion of the CRS in the Party Charter, the CMC Work Rules appear to have been revised again immediately after the Congress when they likely added a statement in the General Provisions that “The CMC [is/are] the Party’s and state’s highest military leadership organ[s], [which] unifiedly lead and command all the nation’s armed forces” (art. 2, 2017).

See Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, 2017, Chinese Military Reform in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications, INSS, pp.32–33.

Either by delegation, as Wuthnow and Saunders put it (2017 p.2; Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, 2019, Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA, p.26); or, under Hu, as a result of loyalty to Jiang, who had promoted the CMC Vice Chairmen and who himself remained powerful as Chairman under Hu (see Joseph Fewsmith, 2021, Balances, Norms and Institutions: Why Elite Politics in the CCP Have Not Institutionalized, The China Quarterly, 248, November 2021, pp.265–282).

Including by Xu Qiliang in his capacity, when writing in 2019, as CMC Vice Chairman.

As opposed to being underpinned by “prospectivity,” or not punishing actions which were legal (or legitimate) at the time when they occurred.

Xu Qiliang, 2019.

This is based on the account of the CMC Work Rules in Ou Jianping 欧建平, 军委主席负责制是中国特色军事领导制度 [The system of the Chairman of the Central Military Commission assuming overall responsibility is a military leadership system with Chinese characteristics]《中国领导科学》China Leadership Science, 2018年第3期.

The Party has both “military Party regulations” (军队党内法规) and “Party military regulations” (军事党内法规), formulated by the CMC and the Party respectively, see Zhu Daokun 朱道坤, 2021, 军事党内法规体系初探 [Preliminary Thoughts on the System of Military-related Intra-party Regulaions], 《党内法规理论研究》Intraparty Regulatory Theory Studies. The table below includes both.

For example, we know there are “provisions” (规定) specifically addressing the CRS. “Provisions,” as a document type, are relatively concrete.

This is derived by triangulating information on the documents in the table below; in particular, the language used in this paragraph is consistently repeated across media reporting and study materials as well as appearing in the Leading Official Press Q&A on the event of the release of one document, see https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-09/10/content_5542390.htm.

Note that “responsibility” (负责) in the CMC Chairman Responsibility System differs from the “responsibility” (责任) in the sense of political responsibility systems (on the latter see Carl Minzner Minzner, Riots and cover-ups: counterproductive control of local agents in China. U. Pa. J. Int’l L. 31 (2009): 53). The former might also be translated as “[to be] in charge” while the latter might be translated as “accountability.” On the “responsibility system related to the CRS see: 10 Sept 2020, 全面加强新时代军队党的建设——中央军委政治工作部领导就《中国共产党军队党的建设条例》答记者问 [Strengthening Party Building in the Military in the New Era: A Q&A Session with a CMC Political Work Department Leader on the “CCP Regulations on Military Party Building”] https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-09/10/content_5542390.htm

See 10 Nov 2023, 强固党指挥枪的根本之举——怎么看深化军委主席负责制贯彻落实 [A fundamental measure to strengthen the Party's command of the gun—How to view the deepening of the implementation of the CMC Chairman Responsibility System] PLA Daily, http://www.81.cn/zt/2023nzt/qmsrxxgcxjpqjsx/sxjd/wgjc/16278110.html.

The full text reportedly also includes “significant adjustments to organizational structure and staffing; budget and final accounts for military expenditures, and expenditures on major projects, and disposal of major assets; research, development, importation, and advancement of major weapons and equipment; major military activities; and important foreign military exchanges.”

See Note 16, Ou Jianping, 2018.

《关于贯彻落实军委主席负责制建立和完善相关工作机制的意见》

See《中国共产党重大事项请示报告条例》[CCP Regulations on Major Item Instruction Requesting and Reporting].

It can also create logjams if too many requests are made.

See Joel Wuthnow, 2019, China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform.

See 林世华 Lin Shihua, 2023, 深刻理解把握“三项机制内涵要求推动军委主席负责制全面贯彻落实 [Understanding the Substance and Requirements of the "Three Mechanisms" and Promoting Comprehensive Implementation of the CRS], 政工学刊 p29.

《中国共产党军队党的建设条例》

See Note 20, 10 Sept 2020, [Strengthening Party Building in the Military].

This should also be understood alongside major institutional reforms such as the disbanding of the General Political Department (See Party Charter 2017 Art.24 as compared to 2012 Art.23.).

19th Party Congress Report.

20th Party Congress Report.

At the time official media announced Xi’s assumption of the “Commander-in-Chief” title in 2016 (https://news.12371.cn/2016/04/20/ARTI1461152230218742.shtml), it was regarded as largely symbolic. Following reforms to disband the general departments, the JOCC had initially been under the CMC Joint Staff Department. But sometime thereafter, before 2022, the relationship between the JOCC and the CMC (and its Joint Staff Department) appear to have changed, meaning the JOCC is subordinate only to the CMC and not to its Joint Staff Department.